It’s generally unwise to use 100% of your account’s buying power for options trading – unless you’re in specific situations where it is okay to lose the entire account.

Such situations might be that you have a segregated account that represents only a small fraction of your total savings.

Or it could be that you are trading a prop firm’s money (or simulated money) in a funded account.

Because options are naturally leveraged, it is not the same as trading a pure stock portfolio.

The P&L swings in options trades do not feel the same as in stock trades.

This is when proper position sizing of options trades becomes important.

Contents

Let’s look at a hypothetical example where the option trader did everything right, except for position sizing.

Suppose an option trader opens a bear call spread on SPX on April 8, 2025, at 12:30 pm EST with SPX at 5139.

This is a reasonable trading thesis, as the market is in a downtrend, as indicated by the downward-sloping 20-day moving average.

These prices for the bear call spread were obtained from the mid-price in OptionNet Explorer’s historical option pricing data.

Sell one contract April 30 SPX 5500 call @ $38.40

Buy one contract April 30 SPX 5525 call @ $32.55

Credit: $585

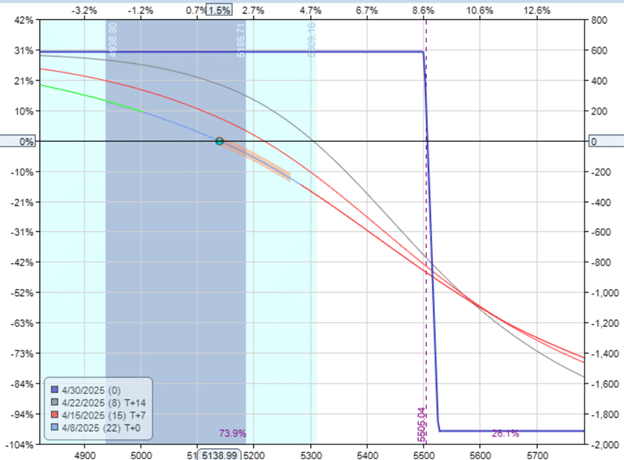

The trader would receive $585 credit for one contract with the following risk graph:

The max risk in this defined risk trade is $1915 as calculated by the width of the spread minus the credit received:

$2500 – $585 = $1915

This gives a risk-to-reward ratio of 3.2, which is reasonable for an out-of-the-money credit spread.

The spread has 21 days till expiration.

The short call is at the 16-delta, about one standard deviation move away from the current price.

This is a textbook example of a bear call credit spread.

The trader is now thinking (as some newer traders might think):

Since this trade has a max loss of less than $2,000, and I have a $10,000 account.

I can trade five contracts and can potentially make five times as much:

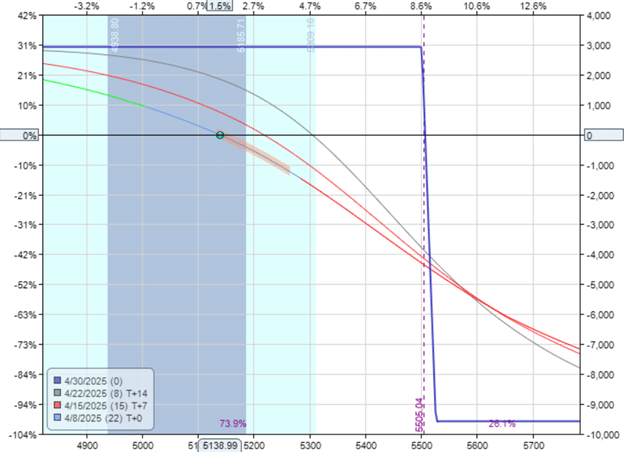

Five contract bear call spread:

Sell five contracts April 30 SPX 5500 call @ $38.40

Buy five contracts April 30 SPX 5525 call @ $32.55

Credit: $2,925

Receiving a credit of almost $ 3,000, the trade now has a maximum risk of $ 9,575:

Let’s see what happens:

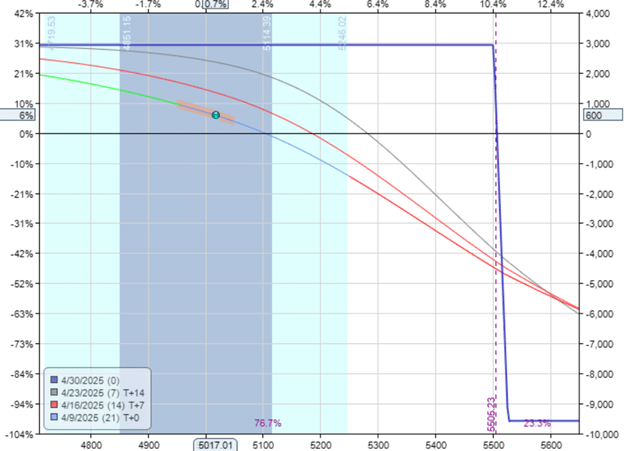

The next day, on August 9, at around 12:30 pm EST, the trader checks his position:

So far, so good. Position is up 6% with a profit of $600.

The trader then goes about his business, stepping away from the computer to exercise or get a haircut.

For a trade that is 21 days till expiration, it is reasonable not to need to be at the screens all the time. Checking once or twice a day should be fine under normal conditions.

Unfortunately, the market can rapidly turn from normal conditions to highly unusual conditions without warning.

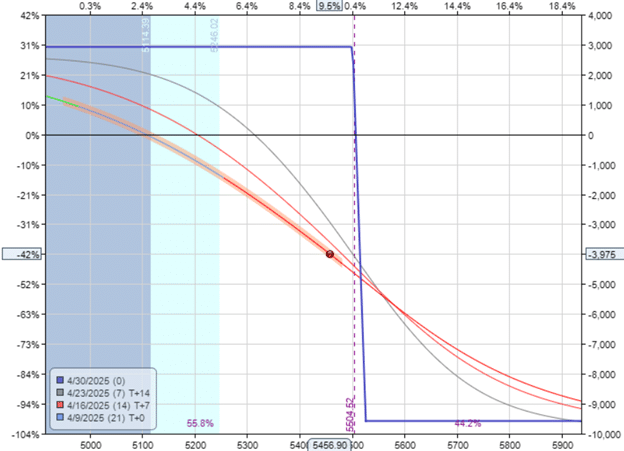

Four hours later, after finishing his lunch and grocery shopping, the trader returns after the market’s regular close and sees that the trade is down $ 3,975.

What happened?

How can the trade be up $600 and now down nearly $4000 in a few hours?

Admittedly, it is rare for SPX to move up 475 points (or 9.5%) in one day:

But on April 9, 2025, it happened.

The trader’s account went down 40% from $10,000 to $6,000 in a matter of hours.

The trader would now need to make a 66% return on the reduced capital of $ 6,000 to return to a balance of $10,000.

If an account has a drawdown of 50%, it would take a 100% return to come back to breakeven.

Even elite traders would have a difficult time making a 66% return in a year. So under the best conditions, a new options trader might need a few years just to recover the loss.

The big mistake that this trader made was that the position size was too large, trading at five contracts.

Even with just one contract, the loss would be $800, representing an 8% portfolio drawdown due to a single trade. Still unpleasant, but at least the account would not be down 40%.

Yet, even one contract on SPX may be too large according to the 2% rule, which says not to let any one trade lose more than 2% of the account.

To follow this advice, the trader with a $10,000 account would need to trade one contract of SPY (one-tenth the size of SPX) with a max risk of $200.

How many such option positions can the trader open up at one time? Or what percentage of the portfolio can the option trader allocate to options trades?

Some sources say only 15% to 30% of a portfolio should be allocated to options.

Other sources indicate that it can reach as high as 50% for income strategies.

Of course, these are rough general guidelines. Everyone has their own individual risk tolerance and circumstances.

If new, start out small so that you become aware of what the market is capable of before it wipes out a large portion of the account (as in our hypothetical trader example).

Then find what is comfortable for you.

Always keep a reserve of cash in an account for position adjustments, margin changes, market shocks, and unexpected events.

We hope you enjoyed this article on allocating a percentage of your account to options trading.

If you have any questions, send an email or leave a comment below.

Trade safe!

Disclaimer: The information above is for educational purposes only and should not be treated as investment advice. The strategy presented would not be suitable for investors who are not familiar with exchange traded options. Any readers interested in this strategy should do their own research and seek advice from a licensed financial adviser.