The following is a true story.

It is not to highlight the unfortunate series of events that occurred to an experienced zero-DTE trader, resulting in a $116,000 loss – a loss that is over three times the defined maximum risk of his original bear call spread.

It serves as a reminder that the market is capable of producing scenarios that we could never anticipate or fully protect against.

Hence, the only mitigation is to keep our position size small.

It is also a lesson to not leg into or out of a vertical spread if you want to keep the spread defined-risk, especially when the CBOE can nullify a filled trade order.

Really?

Yes, it is called a “trade bust”.

Contents

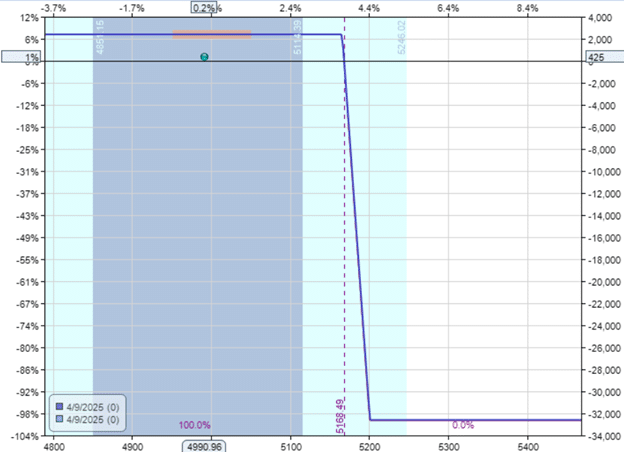

On April 9th, 2025, at 10:30 am CST, Dale Perryman (known as the Iron Fly Guy) initiated the following zero-DTE 5165/5120 bear call spread for 10 SPX contracts.

Recreated in OptionNet Explorer

I don’t think he minds us telling what happened to his zero-DTE trade, since he had broadcast his story on YouTube – partly to get the word out that (in his words):

“This wasn’t a bad trade. This was a good trade, sabotaged by a broken system. Let’s fix it.”

Many traders in the industry had commented on the trade from both sides of the argument.

This is a way out-of-the-money credit spread (below the 10-delta), so the risk-to-reward ratio is approximately 13 to 1 with a maximum defined risk of $32,000.

This is likely suitable for his trading style, skill level, and account size.

He placed the bear call spread as a single order, which is suitable for a defined-risk trade.

After the order was filled and he collected a $ 2,400 credit for the trade, he placed a standing order to take profits on all ten of his short calls, buying to close for a debit of $1.20 per share.

Note that his order was to close just the short calls instead of closing the entire spread consisting of both the short and long legs.

Some zero-DTE traders sometimes do this because the long calls may be too far out of the money and have low value, making it difficult to get filled.

This is known as legging out of a spread. If you leg out by closing the short leg first (which is what Dale did), then the trade remains defined risk.

However, the risk level may change.

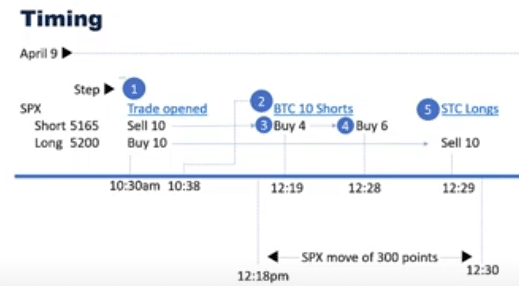

source: YouTube

At 12:19 pm CST, the standing order partially filled four out of the ten contracts.

The platform indicates that four short calls are now closed, with a price of $1.20 per share paid to buy back.

It was around this time that the market started to rally hard upon Trump’s announcement of the pause on tariffs.

Dale scrambled to close the remaining six short calls.

The market was moving rapidly, and bid-ask spreads were becoming very wide.

Because it was easier to get filled on single-leg orders than spread orders, Dale attempted to close just the six short calls first instead of trying to close the spread as a unit.

Nine minutes later, he was able to manually close the remaining six short calls paying a price of $153.50 per share to buy back.

One minute later, he closes the ten long calls selling $91.30 per share.

Based on the fills he was seeing on his platform, everything was closed out, and the trade made a profit of $ 1,120.

Bear call spread initial credit: $2400

Buy to close four short calls ($1.20 each): -$480

Buy to close six short calls ($153.50 each): -$92,100

Sell ten long calls: $91,300

Net profit: $1120

What was odd was how the four short calls were bought back for $1.20, whereas the six remaining short calls cost $153.50 to buy back.

The next morning, five minutes after the market opened, he received a voicemail from his Schwab brokerage stating that the order closing the four short calls was invalid and had been nullified by the CBOE exchange.

CBOE Rule 6.25, informally known as the “Bust Trade Rule,” was designed to protect traders from bad pricing.

A trader or the exchange can invoke this rule if there is bad pricing that harms a trader.

In this case, the trader on the other side of Dale’s trade was harmed because Dale had gotten a very favorable price of $1.20 to buy back the four short calls when the theoretical fair price was much higher.

With that order nullified, it is as if he never closed the four short calls.

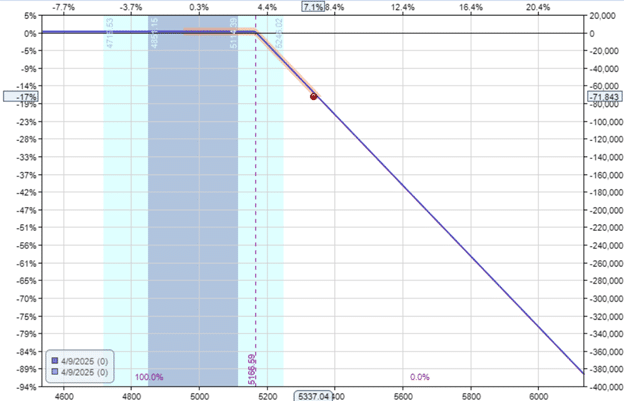

So after his six short calls were closed and the ten long calls were closed, he was still left with four short calls, unbeknownst to him.

Four short calls is a highly dangerous, undefined risk trade that looks like this at 12:30 pm CST…

The market was racing up like it had not done for years (moving over 400 points for the day).

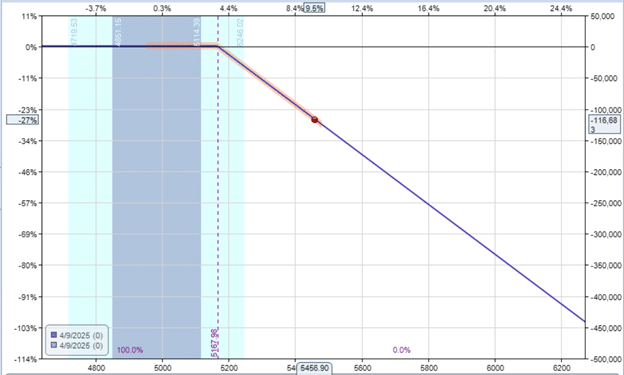

At the end of the day, it had a loss of $116,000, as can be seen below.

What started out as a trade with a defined risk of $32,000 somehow ended in an undefined risk trade with a loss of $116,000.

In hindsight, the $1.20 was indeed bad pricing.

The calls should never have been able to be bought back that cheaply.

But it got filled.

And traders make decisions based on what the platform is telling them.

He closed the protective long calls only after his platform confirmed that all short calls were closed.

How was he supposed to know that four of those short calls would come back into existence?

While Dale had survived the catastrophe, if it were another trader who had a $100,000 account, and this trade only used up one-third of the account’s buying power.

This event would have completely wiped out the account, and the trader would have owed the brokerage money.

What Dale should have done instead of legging out of the spread is to set a limit order to close the spread as a unit (buying back the short and selling the long in one single order).

When executed as a unit, the CBOE could not nullify only one leg of the unit. They would have to nullify the whole unit or not at all.

Therefore, even if a spread order was nullified, the max risk could never exceed the max risk of the spread of $32,000.

Is it fair that the Dale’s fill got nullified after the fact?

If Dale’s fill did not get nullified, is it fair that the other party got really bad pricing?

Did Dale eventually get his money back?

I don’t know the answers to those questions.

But I do know that the market can do some crazy things.

And a series of very unfortunate events can happen (regardless of how rare).

We hope you enjoyed this article on a big loss in a defined-risk options trade.

If you have any questions, send an email or leave a comment below.

Trade safe!

Disclaimer: The information above is for educational purposes only and should not be treated as investment advice. The strategy presented would not be suitable for investors who are not familiar with exchange traded options. Any readers interested in this strategy should do their own research and seek advice from a licensed financial adviser.

**mindvault**

mindvault is a premium cognitive support formula created for adults 45+. It’s thoughtfully designed to help maintain clear thinking