When Japan finally stood on the brink of history—its first female prime minister—it should have been a moment of pride. Instead, Sanae Takaichi found herself at the center of a nationwide witch hunt.

What should have been a celebration of progress turned into a public trial, complete with insults dressed as “feminism” and outrage disguised as “analysis.”

The first female leader wasn’t breaking the glass ceiling. She was being stoned with the shards.

💥The Gender Paradox

It was women who cheered when a female leader was finally within reach—and women who turned against her first.

Across social media, the language was viciously personal:

“Not feminine.”

“A man in disguise.”

“An Abe puppet in lipstick.”

This wasn’t politics. It was policing of gender.

Takaichi’s refusal to perform “soft femininity” violated Japan’s unspoken rule that women in power must still smile sweetly.

She didn’t. And for that, she was branded the enemy of her own sex.

📺The Media Classroom

Turn on the TV, and the lesson was clear: a woman who doesn’t apologize must be arrogant.

Commentators dissected her tone, her posture, even the tilt of her head—never her policy.

One morning show replayed her “angry face” in slow motion, as if emotion disqualified leadership.

If a man slammed his hand on the desk, it was “strong leadership.”

When Takaichi did it, it was “unstable behavior.”

Japan’s glass ceiling is reinforced by microphones and studio lights.

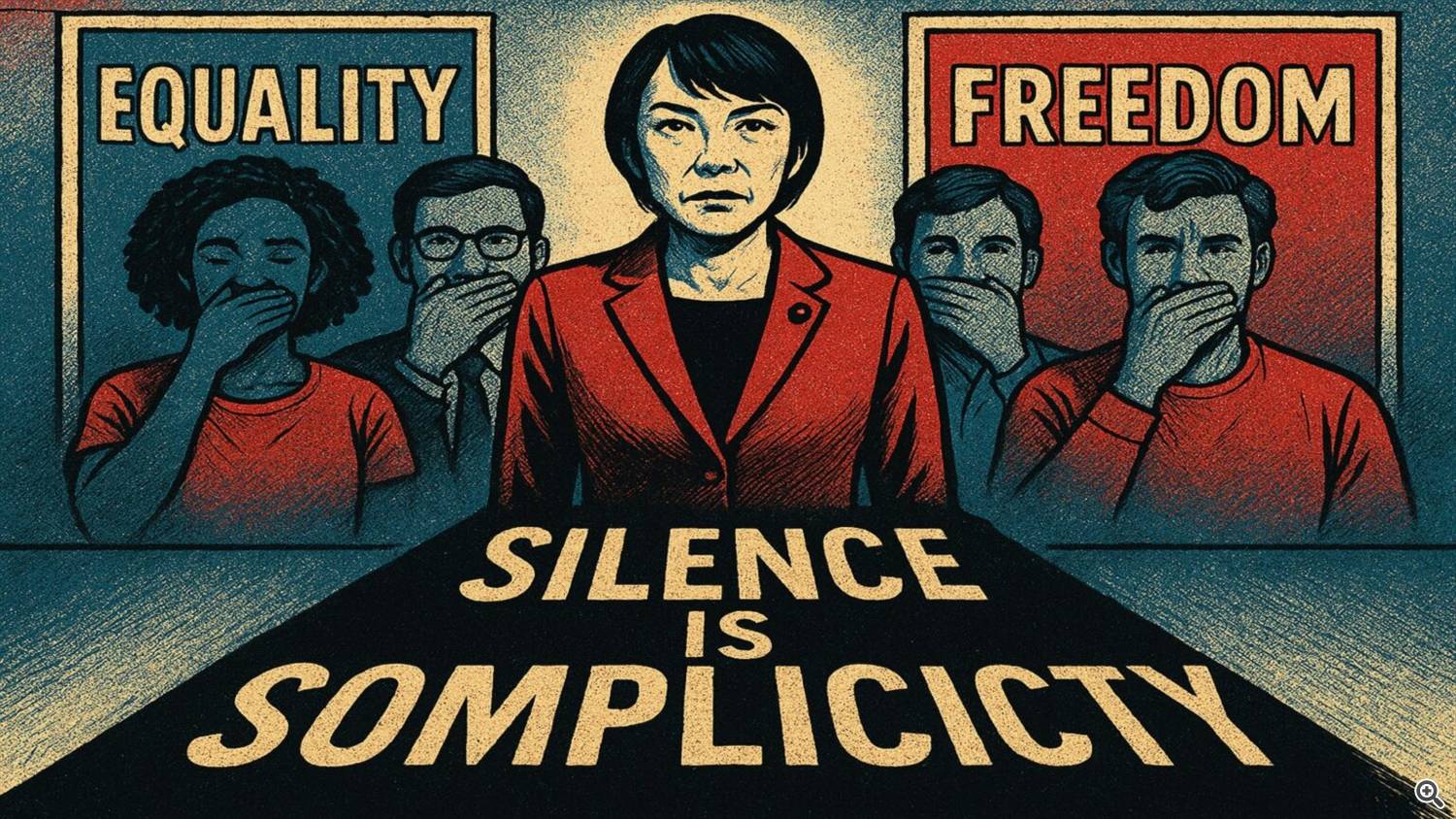

🕳️The Liberal Silence

The most painful betrayal came not from conservatives—but from liberals who claimed to fight for equality.

Where were the gender activists when slurs like “Abe’s doll” flooded X?

Where were the feminist professors when journalists mocked her as “a man in heels”?

They were silent—because the target didn’t fit their ideology.

For Japan’s left-leaning elite, women deserve support only if they conform.

Takaichi’s crime was ideological independence.

In today’s Japan, that’s heresy.

⚖️The Politics of Jealousy

Inside the Diet, the whispers were worse.

Senior women in rival parties mocked her as “too ambitious,” “too proud,” or “too close to the old boys.”

In any workplace, that’s bullying.

In politics, it’s tradition.

Many male politicians privately admitted they feared her competence more than her conservatism.

So they did what Japan’s power networks have always done to strong women:

They isolated her—and called it democracy.

🔁The Double Standards

Japan adores slogans like “womenomics” and “diversity.”

But when a woman actually wins power, she must pass tests no man ever faces.

She must be warm, but not weak.

Tough, but not cold.

Successful, but not threatening.

Fail one of those impossible exams, and the media will remind her of her gender.

“First female prime minister”—every article starts there, and most end there too.

🧩The Real Fear Behind the Hate

What if the outrage isn’t about gender at all—but power?

A woman who doesn’t owe her rise to men, factions, or media patronage is unpredictable.

She can’t be controlled through shame or flattery.

And that makes her dangerous—to the system built by men and maintained by obedient women.

So the attacks continue—not because she’s female, but because she refuses to play the role assigned to her.

🌸Epilogue: The Girl They Couldn’t Break

Sanae Takaichi may yet fail as a prime minister. But if she does, it won’t be because she’s a woman.

It will be because Japan still punishes women who stop apologizing.

Every insult thrown at her says less about her character—and more about ours.

After all, a society that celebrates women’s success only when they obey…

isn’t progressive. It’s performative.

And Japan, once again, has turned the classroom of equality into a schoolyard of bullies.